Q & A: “Better to breed Eclectus parrots in pairs or in a colony?” by Tony Silva

Q & A: “Better to breed Eclectus parrots in pairs or in a colony?” by Tony Silva

Photo courtesy: Kim Forster

In the early 1990s, Australian aviculturists Peter Chapman and Keith Dickins, the owner of Loro Parque Wolfgang Kiessling, and I visited Queensland, Australia. We spent time at Musgrave Station looking at wild Golden-shouldered Parrots (Psephotus chrysopterygius), which nest in peak-shaped terrestrial termitaria, but our focus of that trip and the final destination was even further north than Musgrave–it was the Iron Range. Here are found two species that were on our “must-see” list: the Palm Cockatoo (Probosciger aterrimus) and the Australian Eclectus (Eclectus roratus macgillivrayi).

Peter Chapman, who is an extolled aviculturist and field observer, literally told us the time and location where we would see both. The Palm Cockatoos had come to the ground to drink on the spot and time he indicated. The Eclectus nested in a tree in whose base we set up camp. We could observe the nesting habits of the Eclectus. The days spent with Peter were like watching a movie for the second time: you knew where and when events would occur.

The tree under which we set up our tent had an active Eclectus nest. The female was fed and mated with multiple males. She was like a bee who controlled the hive (the males), calling for food when hungry and mating when she felt it was necessary.

Breed Eclectus parrots: Parrot interview with Laurella Desborough

Those days of observation changed my entire perspective of Eclectus. Before seeing them in the wild, I knew that the female was dominant, that they lack a pair bond–the nexus seen in macaws and cockatoos, for example, which spend long hours preening each other (the hair-like feathers on the head of Eclectus do not require preening for the sheath enveloping the feathers to fall) is not present in Eclectus–and females accept food and the mating advances of multiple males.

This allowed me to experiment with colonies and with trios. In a colony, the females can bicker over a particular nest; I had one crush on the lower mandible of a cage mate, even though they were sisters and had been reared together. In a trio, the hen could pick the male with whom she wanted to mate and she could receive food from both f her consorts.

More pairs of tame Eclectus produce clear eggs than any other group. Every time I visit an aviculturist that has multiple Eclectus I am asked about infertile eggs. In many cases, a quick glance gives me the answer. The male is afraid of the female, never feeding with her, never sitting on the same perch, and avoiding close contact at all cost.

Such males rarely build up the courage to breed. Because of this, I always recommend that when Eclectus are to be kept as pairs, they should be introduced when very young. The female then learns to tolerate the male and as such does not display aggression towards him. I prefer pairing young parent-reared birds but find that hand-reared youngsters reared together also make suitable future pairs.

Pairing adults, perhaps even tame, former pet birds, is a complicated affair. I would recommend acquiring more than one male and housing them with a female. If more than one female is at hand, a simple system can be used: two separate cages, each with one nesting box, can be constructed and interconnected with multiple tunnels. By adding multiple males, the female can pick and choose which male she will accept food from and also mating. This cage also reduces the risk of a female aggressing one particular male, who can flee to the other cubicle. Also, by housing multiple males together they seem to build up the courage to confront a female who may turn bellicose.

If only one cage is available, then a solid board should block the view of the next nests; females tend to perch with the head emerging from the nest and if they can see each other, they are more prone to fight.

With Eclectus, it is important to pair birds of the same subspecies. Unless this is done, eventually aviculture will be confronted with a single hybrid species–a domesticated Eclectus whose genetic constitution is composed of multiple races.

With the likelihood of wild imports ever again appearing to be virtually nil, maintaining subspecies integrity is very important.

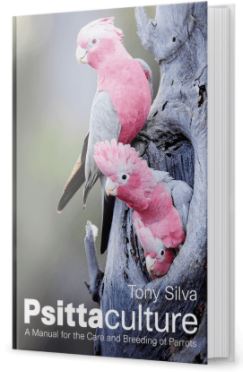

Tony’s book Psittaculture, is available from:

ALL TONY’S ARTICLES ARE AVAILABLE IN THIS eBook, available to subscribers: Including this blog post, “Better to breed Eclectus parrots in pairs or in a colony?”

Click on cover for more information on what you get for subscribing:

I have a tremendous respect for Tony Silva and his work with birds. But, as a long time eclectus breeder, I want to comment re two points: 1) Female eclectus in Australia have displayed certain behaviors in terms of taking food from various males and mating with more than one male (which MIGHT be ritual mating which has been observed with other parrot species, such as the Greater vasa, and also observed with other avian species, including finches in the UK), but that does not indicate that ALL eclectus subspecies behave in this manner re mating. To my knowledge there have been no research studies or biologist’s observations to confirm this process occurs with other eclectus subspecies. 2) In terms of facilitating successful mating and breeding behavior with eclectus parrots in our aviaries, IME it is not a good idea to rear a young male and female together from an early age as they MAY consider each other to be clutch mates. (See other resources for the science on mate selection and avoiding mating with clutch mates.) IME it is critical that males KNOW how to mate, not just that a male is paired with a female. IF males are hand reared they need to be flocked immediately after weaning with other young of both sexes and allowed to become adults in that situation. Upon reaching adulthood, flocked eclectus males and females will SELECT the individual with whom they will bond and mate. We use this procedure with our many eclectus parrots and it works. A major problem, not just with eclectus parrots but with many parrots, is that after hand rearing the individual birds are NOT flocked with conspecifics and thus grow up without learning appropriate socialization. The end result is males that are not only fearful of interacting with females, but males that have NO CLUE about how to mate with a female even when the female is willing to mate. I have a couple pairs like that which were acquired from other sources. These males LOVE their mates and will preen and caress the female when she requests the male to mate with her, but they will not copulate with the female and display no indication that they understand how to mate.

Hi Laurella, it’s such a great honor hearing from you and for providing such informative feedback. I am sure Tony will also appreciate it. I would love to hear from you more and you are very welcome to email me for any articles and information I can publish in the magazine and as a blog post.

Many thanks again.